If you’ve ever hunted for information on Reach Mahjong on the internet, chances are you’ve read of, or about, Benjamin Boas. Today we’re taking an in-depth look at Ben, one of mahjong’s most respected international players.

History

Ben has been involved in mahjong since 2004. At that time there was very little to read in English about reach mahjong strategy. Ryan Morris’ “Mahjong for Dummies”, a couple of chapters in the Eleanor Noss Whitney book “A Mah-jong Handbook”, and American mahjong legend Tom Sloper’s Sloperama were the only places to read anything other than the most basic reach mahjong rules.

At that time, Ben, already a lifelong Japanese culture aficionado, was backpacking in Tibet. During a nighttime downpour, he found solace in the only building with lights on – where locals where playing a game of mahjong. Knowing no common language between them, he learned the game through pantomime, and went from that one night of wins, through a winding path of watching pro players in arcades and parlors across Japan, into being known as a world-renowned mahjong culture writer and historian.

In 2007, thanks to Reach-Mahjong.com and the internet popularity of the works of Nobuyuki Fukumoto, anexplosion of English-language mahjong reading became available. With people fueled to learn more about the game to better enjoy mahjong-related stories, more and more information began to appear online. At that time, Ben placed third in the European Open MCR Championship – one of the first international Japan-related tournaments, and the next year second in the Reach Rules division.

“’07 wasn’t actually the first international event – Kyouichirou Noguchi, founder of Takeshobo, publisher of Kindai Mahjong, was sponsoring tournaments since 2002. He also underwrote the Mahjong Museum, and paved the way for the tournaments to come,” Ben explains.

“MCR rules were Japan thinking that outsiders would not want to play the high-skill based, push-pull game of Reach, and opted to back a hybrid ruleset. How surprised was it that Reach itself would become so popular over here. It is a unique example of how fictional dramas could be heightened by a proper game.” Unlike many other fictional stories that revolve around a game (such as chess), where board positions are incorrect or arbitrary, and games are explained to the viewer so they don’t need to know the game to enjoy the show to its fullest, there are actually companies, such as Babylon, that exist solely to properly set up the “tile fight” so that the in-world games complement and heighten the main story.

Ben goes on to explan the ‘humanization’ of mahjong manga. “In the seventies, ‘mahjong manga’ were short stories of, invariably, an invincible protagonist that wins improbable hands and [has his way] with women. However, in mahjong, you lose more hands than you win, and as mahjong fiction changed to more accurately depict the game – fallible heroes that don’t always succeed.”

This led to an increase in not only readership, but the breadth of *types* of readership. With more enjoyable and relatable stories, more types of people were drawn to it, and in turn to mahjong itself. While manga might not necessarily improve your game (an important exception is Obaka Miiko, Masayuki Katayama’s most popular work – more on him shortly!), it leads to drive to play more, and any competitive spirit will naturally lead to the want to improve.

Mahjong Skill

Improving sounds like it would be a simple matter, but “getting used to certain playgroups” and relative strengths means you may not have the opportunity to get better through playing the same groups of players. You might be so much better than your compatriots that you can’t find any room to improve further, so much less skilled that you don’t know why other players do what they do, or even be so used to certain styles that it clouds your understanding of what you need to do to improve. In those situations, Ben has some important advice.

“If anyone wants to get a real test of their skill level, the gold standard is playing at cash parlors in Japan”.

Players in “rate” parlors (parlors where you play for a certain amount of money per point) are always out to win, have something on the line, and the continual flow of playres means you have to adapt again and again if you don’t want to go broke. So, if you aren’t sure how good you are, stop by a parlor sometime, and find out!

The Good Players’ Club

“The name sounds a lot cooler in Japanese.”

Ben is a member of the Good Players’ Club – GPC for short – is an organization founded on three rules: good players keep other people in mind, good players are only hard on themselves, and good players play with a good mood. Started in 2009 by Masayuki Katayama and Hirokazu Baba (“The best mahjong player, and the most popular mahjong commentator, in the world” according to Ben), it has grown into two celebrity leagues and even more open leagues, showcasing both famous top-talent players, mangaka (Nobuyuki Fukumoto of Akagi fame and previously-interviewed Shinasaka Kouji), all enjoying and promoting mahjong as a fun activity in Japan and beyond. Katayama is also a famous mangaka in his own right, writing many popular and informative titles.

“In order for mahjong to grow, the absolute most important thing is for people to have fun!”, Ben explains. While professional leagues and parlors offer unique competitive experiences, a consistent feeling of having a good time is more likely to turn a ‘sometimes’ player into a lifelong fan.

They also run prestigious yearly tournaments – of which Ben won the first one, followed by Ryan Morris back-to-back, making Americans three-time winners of the event.

Katayama himself has won, and not just in the celebrity division – he plays in the non-celebrity division as well, still managing to take home the gold as a regular player.

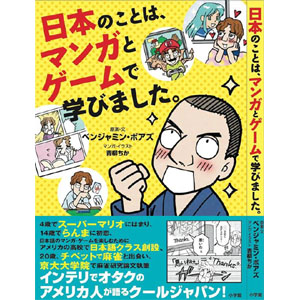

If you are interested in more, you can check out Ben’s excellent book (a one-shot manga, and actually a pretty easy read if you are just learning Japanese yourself!), entitled “日本のことは、マンガとゲームで学びました。” (“I learned about Japan from Manga and Games”), which highlights a number of personal, funny stories straight from Ben’s adventures in Japan. You can pick up a copy from Amazon Japan – it’s worth every yen! You can also find Ben at his website, BenjaminBoas.com.